The world is currently experiencing a severe disparity in wealth and opportunity, but it does not stop there; health and exposure to disease are also determined based on where you are born. The rich world typically has the luxury of living with even the most dangerous diseases thanks to advances in and access to medicinal innovations. The same disease in a poorer country can mean a death sentence, because medical treatment—that is proven to work for those rich enough to pay for it—is compromised or unavailable entirely. Third world countries struggle to achieve positive health outcomes, but some diseases are particularly aggressive and define the lives of the people who live in these less fortunate regions.

The Most Common Diseases

Throughout the third world regions of Africa and Asia, three diseases in particular ravage the population and leave little room for treatment: malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS. Where a rich person can continue on with life after HIV/AIDS by taking medicine, this illness is almost entirely untreated in the poorer regions of the world. Tuberculosis is essentially unheard of in first world countries, and vaccination has slowed or even stopped the spread of germs that have the potential to wipe out entire communities of children in some parts of Africa and Asia.

In the developing world, up to half of all deaths are due to infectious diseases. AIDS has cut the life expectancy of some countries nearly in half, with Botswana seeing a drop from 62 years old (in the 1980s) to only 37 due to the high rate of HIV infection: about 39% of all people in the country. Across sub-Saharan Africa, the life expectancy remains at a low 47 years of age on average.

Poverty plays a primary role in why these regions of the world are primarily infected. Affluent countries have no issue with affording the drugs that suppress HIV, but those medicines—and even more inexpensive options to treat only the infections resulting from their weakened immune systems—are unavailable to poorer countries. Tuberculosis takes advantage of the widespread HIV epidemic to proliferate itself, latching on to those with already weakened immune systems. Up to 15% of HIV cases die as a result of TB.

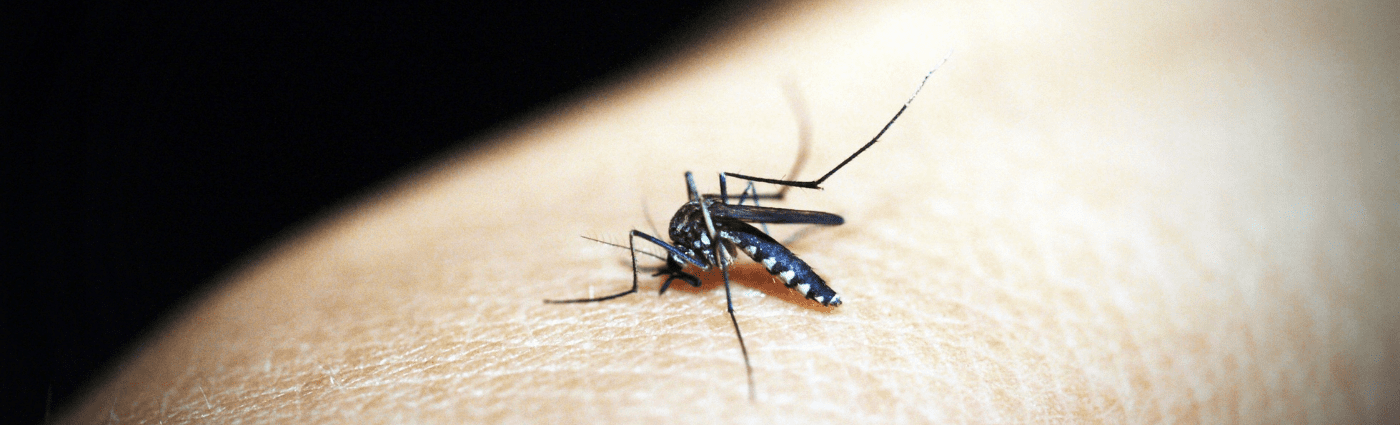

Malaria also plays a significant role in health outcomes of third world countries. Transmitted via the bite of the Anopheles mosquito, malaria causes more than one million deaths per year—90% of which are in sub-Saharan Africa. It is highly resistant to many antibiotics that have previously been used to treat it, and this trend is not anticipated to slow down any time soon. For residents of developing countries that do not have access to newer treatments, this constantly evolving disease is an ever present threat.

The Cost of Fighting

It is the responsibility of richer countries to assist in fighting disease in the developing world. Some solutions are simple and inexpensive, such as mosquito nets infused with insecticide. Simply installing these in sample regions has cut the number of malaria deaths by 20%. The UN has noted that affluent countries pay a fraction of the cost for medicines that the poorest in the world would be entirely unable to pay for, and NGOs like Action Aid have maintained consistent lobbying to cut drug prices.

Anti-retroviral drugs that keep people with HIV alive cost nearly $10,000 in developing countries, but thanks to the efforts of organizations like Action Aid, the price has been brought down to about $300. This is still prohibitively expensive in many of the world’s poorer areas, but the price is anticipated to continue downward. UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan established the Global Fund for HIV/Aids, TB and Malaria, though affluent countries have been stingy to contribute toward its yearly $7 billion goal, with the US sending only $500 million.

Market Incentivization and What to Do

One of the largest problems facing the treatment of these diseases is the lack of incentive to focus on them from a market standpoint. Out of 1393 new medicines that were approved for public use, only 16 focused on tropical diseases like TB. A drug for sleeping sickness, which kills an average of 66,000 people per year, saw its production halted when no one was buying it—because it was too expensive for the developing countries that needed it. However, it was rebranded for use in the United States, where it is now used frequently as a hair remover.

Drug companies must be incentivized to continue or focus on production of critical, life-saving medications even when poorer countries cannot afford them. This will require significant policy change in the government as well as the support of normal people, who can contribute by donating to charities that provide monetary assistance to underprivileged areas.